Table of Contents

Angular

A really cool tutorial: https://speakerdeck.com/toedter/cool-web-apps-with-spring-boot-angular-and-typescript

Tools

The tools for angular development.

| Tool | Input | Description |

|---|---|---|

| npm | package.json | Package manager. Resolves dependencies. \\Runs scripts. |

| webpack | webpack.config.js | Package CSS. Minify, uglify. |

Syntax

let

use let to declare variables.

Dont use var, it sometime doesnt respect the scope, like in for loops.

Typescript resolves the conflicts between scopes on its own, when using let

the code, when compiled

var let = 3;

for (let i_1 = 0; i_1 < 10; i_1++) {

}

gives

var i = 3;

for (var i_1 = 0; i_1 < 10; i_1++) {

}

primitives

// number // defines a floating-point number, as well as hexadecimal, decimal, binary, and octal literals. age: number = 7; height: number = 5.6; // boolean const isZeroGreaterThanOne: boolean = false; //array brand: string[] = ['Chevrolet', 'Ford', 'General Motors']; // any // dynamic typing with any type let distance: any; distance = '1000km'; distances: any[] = ['1000km', 1000]; // custom types type Animal = 'Cheetah' | 'Lion'; animal: Animal = 'Cheetah'; //Type '"Turtle"' is not assignable to type 'Animal'. const animal: Animal = 'Turtle'; //Type inference //Typing is optional since TypeScript is smart enough to infer the data types of variables and function return values out of context const brand = 'Chevrolet';

Enums

// enum

enum Brands { Chevrolet, Cadillac, Ford, Buick, Chrysler, Dodge };

myCar: Brands = Brands.Cadillac

// Inspecting the value of myCar returns 1 (which is the index held by Cadillac)

enum BrandsReduced { Tesla = 1, GMC, Jeep };

const myTruck: BrandsReduced = BrandsReduced.GMC;

//Inspecting myTruck yields 2, since the first enumerated value, Tesla, was set to 1

already.

// We can extend value assignation to all the enum members as long as such values are integers

enum StackingIndex {

None = 0,

Dropdown = 1000,

Overlay = 2000,

Modal = 3000

};

const mySelectBoxStacking: StackingIndex = StackingIndex.Dropdown;

enum Brands { Chevrolet, Cadillac, Ford, Buick, Chrysler, Dodge};

const myCarBrandName: string = Brands[1];

//from TypeScript 2.4 and onward, it is possible to assign

string values to enums.

enum StackingIndex {

None = "eins",

Dropdown = "zwei",

Overlay = "drei"

};

// void

function test(): void {

const a = 0;

}

ts

create a helloworld typescript app, save as hello.ts

let greet: string = "Greetings"; let geeks: string = "Geeks For Geeks"; console.log(greet + " from " + geeks); // save the file as hello.ts

Install and transpile

npm install -g typescript tsc hello.ts

run

node hello.js

run without binding to the host name

ng serve --port 8003 --host 0.0.0.0

run with polling

ng serve --poll 500

Watch changes in code and auto rebuild

ng build --watch --poll 500 --configuration development

To check if any module in a project is 'old': npm outdated.

To update all dependencies, if you are confident this is desirable: npm update.

To update all dependencies, if you are confident this is desirable: npm update xml2js.

To update package.json version numbers, append the –save flag: npm update –save.

ng build --watch --poll 500 --configuration development

add a dependency package to your project. E.g. `@angular/material`

ng add @angular/material

functions

function sayHello(name: string): string {

return 'Hello, ' + name;

}

// bind to variable

const sayHello = function(name: string): string {

return 'Hello, ' + name;

}

// this is how to mention the type of var with function

const sayHello: (name: string) => string = function(name:

string): string {

return 'Hello, ' + name;

}

// optional parameters are marked with ?

function greetMe(name: string, greeting?: string): string {

if(!greeting) {

greeting = 'Hello';

}

return greeting + ', ' + name;

}

// Be aware that optional parameters should be placed last

// This creates a situation where both parameters would be considered mandatory.

function add(optional?: number, mandatory: string) {}

// Default parameters

function greetMe(name: string, greeting: string = 'Hello'):

string {

return `${greeting}, ${name}`;

}

// One of the big advantages of the flexibility of JavaScript when defining functions is

// its ability to accept an unlimited non-declared array of parameters in the form of the

// arguments object. In a statically typed context such as TypeScript, this might not be

// possible, but it is actually using the rest parameter's object. We can define, at the end of

// the arguments list, an additional parameter prefixed by ellipsis ... and typed as an array:

function greetPeople(greeting: string, ...

names: string[]): string {

return greeting + "," + names.join("and") + "!";

}

// lambdas alias "fat arrow functions" in angular

const double = x => x * 2;

double(5) // returns 10

let addAndDouble = (x, y) => {

const sum = x + y;

return sum * 2;

}

addAndDouble(1,2) // makes 3

// lambda without parameters

() => console.log("Hello " + this.name)

// lambdas are anonmous, they dont change value of "this"

// here a non anonymous function is used for logging

// but it changes the "this" to "greet = function()"

function delayedGreeting(name): void {

this.name = name;

this.greet = function(){

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Hello " + this.name);

}, 0);

}

}

const greeting = new delayedGreeting("John");

greeting.greet(); // Hello "undefined"

// you can use the "ugly hack" with "that"

function delayedGreeting(name): void {

this.name = name;

this.greet = function(){

const that = this; // <--- Ugly Hack!!!

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Hello " + that.name);

}, 0);

}

}

const greeting = new delayedGreeting("John");

greeting.greet(); // Hello John

//instead you can use a lambda, as its anonymous and doesnt change scope of this

function delayedGreeting(name): void {

this.name = name;

this.greet = function() {

setTimeout(() =>

console.log("Hello " + this.name)

, 0);

}

}

const greeting = new delayedGreeting("John");

greeting.greet(); // Hello John

merge

Merge an item with an array

const newItem = 3;

const oldArray = [1, 2];

const newArray = [...oldArray, newItem];

const oldPerson = { name : 'John' };

const newPerson = { ...oldPerson, age : 20 };

template strings

const url =

`${baseUrl}/${path_to_

resource}?param=${parameter}¶m2={parameter2}`;

generics

// declare a generic argument arg

function method<T>(arg: T): T {

return arg;

}

// express that the arg must be a number

method<number>(1);

// CustomPerson is also an array

class CustomPerson extends Array {}

class Person {}

// or an array of persons is an array

const people: Person[] = [];

const newPerson = new CustomPerson();

/ both is accepted in above "method"

method<Person>(people);

method<CustomPerson>(newPerson);

You can use “extends”

interface Shape {

area(): number;

}

class Square implements Shape {

area() { return 1; }

}

class Circle implements Shape {

area() { return 2; }

}

// any amount of args which are an array of something, what extends "Shape"

function allAreas<T extends Shape>(...args: T[]): number {

let total = 0;

args.forEach (x => {

total += x.area();

});

return total;

}

allAreas(new Square(), new Circle());

classes

- Property members in a class come first, and then a constructor and several methods and property accessors follow.

- None of them contain the reserved function word,

- and all the members and methods are annotated with a type, except constructor.

class Car {

private distanceRun: number = 0;

private color: string;

constructor(private isHybrid: boolean, color: string =

'red') {

this.color = color;

}

getGasConsumption(): string {

return this.isHybrid ? 'Very low' : 'Too high!';

}

drive(distance: number): void {

this.distanceRun += distance;

}

static honk(): string {

return 'HOOONK!';

}

get distance(): number {

return this.distanceRun;

}

}

- Members: Any instance of the Car class will contain three properties: color typed as a string, distanceRun typed as a number, and isHybrid as a boolean. Class members will only be accessible from within the class itself. If we instantiate this class, distanceRun, or any other member or method marked as private, it won't be publicly exposed as part of the object API.

- Constructor: The constructor executes right away when we create an instance of the class. Usually, we want to initialize the class members here, with the data provided in the constructor signature. We can also leverage the constructorsignature itself to declare class members, as we did with the isHybrid property. To do so, we need to prefix the constructor parameter with an access modifier such as private or public. As we saw when analyzing functions in the previous sections, we can define rest, optional, or default parameters, as depicted in the previous example with the color argument, which falls back to red when it is not explicitly defined.

- Methods: A method is a special kind of member that represents a function and, therefore, may return a typed value. It is a function that becomes part of the object API but can be private as well. In this case, they are used as helper functions within the internal scope of the class to achieve the functionalities required by other class members.

TypeScript eliminates this boilerplate of using “this.make=make” by using

accessors on the constructor parameters.

You can now type the following and TypeScript will create the respective public fields and make the assignment automatically.

class Car {

constructor(public make: string, public model: string) {}

}

Interfaces

enforcing the existence of specific fields, as well as methods in classes .

interface Vehicle {

make: string;

}

class Car implements Vehicle {

make: string;

}

An interface may contain optional members as well.

The following is an example of defining an Exception interface that contains a required message and optional id property members:

interface Exception {

message: string;

id?: number;

}

One can instantiate anonymous interfaces. This is interesting because there are no classes involved. This means you can create a mocking library very easily.

interface A {

a

}

const instance = <A> { a: 3 };

instance.a = 5;

mocking interfaces

interface DatabaseService {

save(order: Order): void

}

...

new OrderProcessor(mockLibrary.mock<DatabaseService>());

Where in other languages we need to bring in a mock library as a dependency, in TypeScript, we can utilize a built-in construct by typing the following.

This creates an instance of DatabaseService. However, be aware that you are responsible for adding a process method to your instance because it starts as an empty object.

const databaseServiceInstance = <DatabaseService>{};

Decorators

Decorators - are declared annotations.

Decorators - can extend existing class / functions with new methods etc. They are breaking encapsulation of classes.

declare type ClassDecorator = <TFunction extends Function>(Target:TFunction) => TFunction | void;

For Classes

function Banana(target: Function): void {

target.prototype.banana = function(): void {

console.log('We have bananas!');

}

}

@Banana

class FruitBasket {

constructor() {}

}

const basket = new FruitBasket();

// basket.banana(); wont compile, as compiler enforced declaration of methods in FruitBasket. Cast to "any"

(basket as any).banana(); // avoid compiler error. Call Decorator method.

Decorators can receive arguments, like a string message

function Banana(message: string) {

return function(target: Function) {

target.prototype.banana = function(): void {

console.log(message);

}

}

}

@Banana('Bananas are yellow!')

class FruitBasket {

constructor() {}

}

As a rule of thumb, decorators that accept parameters

- require a function whose signature matches the parameters we want to configure (here Banana(String:message)

- and returns another function whose signature matches that of the decorator we want to define (here banana())

Method decorators

function Log(){

return function(target, propertyKey: string, descriptor:

PropertyDescriptor) {

const oldMethod = descriptor.value;

descriptor.value = function newFunc( ...args:any[]){

let result = oldMethod.apply(this, args);

console.log(`${propertyKey} is called with ${args.

join(',')} and result ${result}`);

return result;

}

}

}

class Hero {

@Log()

attack(...args:[]) { return args.join(); }

}

const hero = new Hero();

hero.attack();

parameter of functions can be decorated

function Log(target: Function, key: string, parameterIndex:

number) {

const functionLogged = key || target.prototype.constructor.

name;

console.log(`The parameter in position ${parameterIndex} at

${functionLogged} has been decorated`);

}

class Greeter {

greeting: string;

constructor (@Log phrase: string) {

this.greeting = phrase;

}

}

You have probably noticed the weird declaration of the functionLogged variable. This is because the value of the target parameter varies, depending on the function whose parameters are decorated. Therefore, it is different if we decorate a constructor parameter or a method parameter. The former returns a reference to the class prototype, while the latter returns a reference to the constructor function. The same applies to the key parameter, which is undefined when decorating the constructor parameters.

Parameter decorators do not modify the value of the parameters decorated or alter the behavior of the methods or constructors where these parameters live. Their purpose is usually to log or prepare the container object for implementing additional layers of abstraction or functionality through higher-level decorators, such as a method or class decorator.

Partial

interface Hero {

name: string;

power: number;

}

const hero: Partial<Hero> = {

name: 'Iron man'

}

Union class

We've alrady learned about generics and how they help us when we want to mix types. A nice alternative, when we know what the possible types are, is the Union type.

interface Hero {

name: string;

powers: number[] | Record<string, number>;

}

Nulable

To indicate that a property is nullable

interface Hero {

powers: number[] | null | undefined;

}

The {[key: string]: string} type in TypeScript.

The {[key: string]: string} syntax is an index signature in TypeScript and is used when we don't know all the names of a type's properties ahead of time, but we know the shape of the values.

// function returning index signature

// (a key-value structure with key and value strings)

function getObj(): { [key: string]: string } {

return { name: 'Bobby Hadz', country: 'Chile' };

}

// Interface using index signature

interface Person {

[index: string]: string;

}

// const p1: Person

const p1: Person = { name: 'Bobby Hadz', country: 'Chile' };

Usage of Type Animal. Accepts properties with type “String” and value also “String”

// 👇️ Type using index signature

type Animal = {

[index: string]: string;

};

const a1: Animal = { name: 'Alfred', type: 'dog' };

Here the compiler wont create a property with a value “number”.

interface Person {

[index: string]: string;

}

// ⛔️ ERROR: Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'string'.

const p1: Person = { name: 'Bobby', age: 30 };

But you can fix it, by allowing string OR number.

interface Person {

[index: string]: string | number;

age: number;

name: string;

}

// 👇️ const p1: Person

const p1: Person = { name: 'Bobby', country: 'Chile', age: 30 };

Readonly

You can also set an index signature to readonly if you need to prevent assignment to their indices.

interface ReadonlyObj {

readonly [index: string]: any;

}

// 👇️ const p1: Person

const p1: ReadonlyObj = {

name: 'Bobby Hadz',

};

// ⛔️ Error: Index signature in type 'ReadonlyObj'

// only permits reading.

p1.name = 'James';

apply CSS classes

Single class

<p [class.star]="isLiked"></p>

Many classes

<p [class]="currentClasses"></p>

// object variable will be evaluated to star-class, as its true

currentClasses = {

star: true,

active: false

};

Event binding

An event binding listens for DOM events (It supports native DOM events that can be found at https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Events) that occur on the target HTML element and responds to those events by calling corresponding methods in the component.

The event inside parentheses is called the target event (click) and is the event that we are listening to.

The variable on the right is called the template statement and corresponds to a public method of the component. In this case, when the user clicks the button, the component calls the `onClick()` method.

// syntax ..(event)="template_statement".. // example <button (click)="onClick()">Click me</button>

In the previous diagram, you can see an overview of how the component interacts with its

template bidirectionally.

In the previous diagram, you can see an overview of how the component interacts with its

template bidirectionally.

Input binding example

input binding is used when we want to pass data between components. This method is applicable in scenarios where we have two components, one that acts as the parent component and the other as the child.

—

A new component “alf-component1” :

app/alf-component1/alf-component1.component.spec.ts

import {Component, Input} from '@angular/core';

@Component({

selector: 'app-alf-component1',

templateUrl: './alf-component1.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./alf-component1.component.css']

})

// export - makes component public. So its selector becomes includable in other components

export class AlfComponent1Component {

// allows to pass the "name" to the selector

// as <app-alf-component1 [name]="hero"></app-alf-component1>

@Input() public name: string;

}

Because a field “name” exists in component - I can use it in the template:

app/alf-component1/alf-component1.component.html

<p>alf-component1 and {{name}} works!</p>

— Default “root” component

app/app.component.ts

Define a “title” field.

@Component({

selector: 'app-root',

templateUrl: './app.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./app.component.css', './app.component.custom.css', './app.component.gears.css', './app.component.icon.css', './app.component.icon.linkedin.css', './app.component.icon.blog.css']

})

export class AppComponent {

title = 'Business Card';

}

Because the @Input was used on name- I can pass name as argument,

to the selector of component “alf-component1”,

when using the “alf-component” selector in another context.

And I bind the title field of root component to it.

app/app.component.spec.ts

<app-alf-component1 [name]="title"></app-alf-component1>

Output binding example

—

A new component “alf-component1” :

app/alf-component1/alf-component1.component.spec.ts

import {Component, Input} from '@angular/core';

@Component({

selector: 'app-alf-component1',

templateUrl: './alf-component1.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./alf-component1.component.css']

})

// export - makes component public. So its selector becomes includable in other components

export class AlfComponent1Component {

// Output - allows to LISTEN for changes, when the selector of this component is used

@Output() liked = new EventEmitter<boolean>();

}

Because a field “liked” exists in component - I can use to emit events:

app/alf-component1/alf-component1.component.html

<!-- Emitting the event only. The logic will be at the place, listening for the event. --> <button (click)="liked.emit(true)">Like</button>

Define a “onLike” method.

@Component({

selector: 'app-root',

templateUrl: './app.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./app.component.css', './app.component.custom.css', './app.component.gears.css', './app.component.icon.css', './app.component.icon.linkedin.css', './app.component.icon.blog.css']

})

export class AppComponent {

onLike($event:boolean){

window.alert(`I like ${this.title}`)

}

}

Because the @Output was used on liked- I can bind to events of liked,

when using the “alf-component” selector in another context.

And I bind the onLiked() method of root component to those events.

app/app.component.spec.ts

<app-alf-component1 (liked)="onLike($event:boolean)"></app-alf-component1>

Local references ( template reference variable )

In selectors of components - you can tag the component instance.

Then you will be able to access its properties directly. Syntax #TAGNAME

<app-hero [name]="hero" #heroCmp (liked)="onLike()"></app-hero>

<span>{{heroCmo.name}}

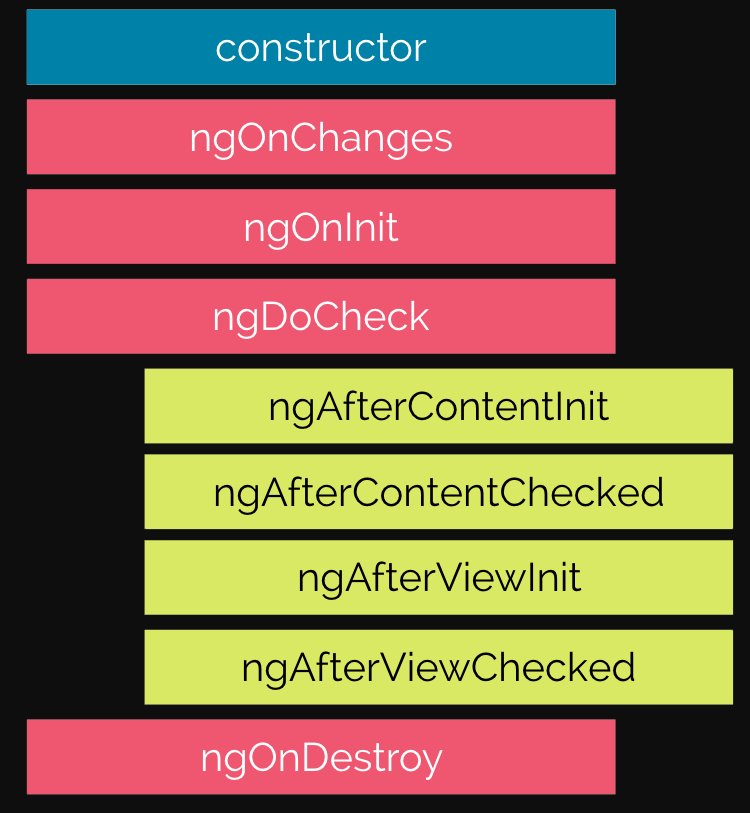

Lifecycle of a component

Lifecycle hooks are used, by implementing an interface.

export class HeroComponent implements OnDestroy, OnInit {

@Input() name: string;

@Output() liked = new EventEmitter();

constructor() { }

ngOnInit(): void {

}

ngOnDestroy() {

}

}

Available intrefaces

- OnInit

- OnDestroy

- OnChanges

- DoCheck

- AfterContentInit

- AfterContentChecked

- AfterViewInit

- AfterViewChecked

Pipes and directives

- Components are directives with an associated template.

- Structural directives add or remove elements from the DOM.

- Attribute directives modify the appearance or define a custom behavior of a DOM element.

One can build custom directives.

Structural Directives

ngIf

If the expression evaluates to true, the element is inserted into the DOM. Or removed otherwise.

<p *ngIf="name === 'Boothstomper'">

{{name}} hero works!</p>

// this just HIDES the element but keeps it in DOM

<p [hidden]="name !== 'Boothstomper'">{{name}} hero works!</p>

It is recommended to use ngIf when dealing with a large amount of data

You can fall back to a default, when evaluated to “false”.

<p *ngIf="name === 'Boothstomper'; else noHero">

{{name}} hero works!

</p>

<ng-template #noHero>

<p>Hero was not found</p>

</ng-template>

The noHero variable is a template reference variable. displayed on the screen only when the else statement becomes active.

ngFor

iterates through a list of items and binds each item to a template.

One can access properties of object like “hero”.

Additional properties are available:

- index indicates the index of the item in the array, starting at 0 (number).

- first/last indicates whether the current item is the first or last item of the

array (boolean).

- even/odd indicates whether the index of the item in the array is even or

odd (boolean).

<li *ngFor="let hero of heroes; property as variable"></li>

During the execution of ngFor, data may change, elements may be added or removed, and even the whole list may be replaced. Angular must take care of these changes by creating/removing elements to sync changes to the DOM tree.

ngSwitch

switches between templates within a specific set and displays each one depending on a condition.

<div [ngSwitch]="hero.team">

<div *ngSwitchCase="'avengers'">{{hero.name}} is avenger</

div>

<div *ngSwitchCase="'villains'">{{hero.name}} is villain</

div>

<div *ngSwitchDefault>{{hero.name}}</div>

</div>

Custom directives

generate file

ng generate directive copyright

declare

@Directive({

selector: '[appCopyright]'

})

apply

<p appCopyright></p>

Pipes

One can pass transformation functions via pipes.

<ul>

<li *ngFor="let hero of heroes | sort:'name'">

{{hero.name}}

</li>

</ul>

One can create own pipes.

ng generate pipe sort

@HostBinding and @HostListener

- @HostBinding binds a value to the property of the native host element.

- @HostListener binds to an event of the native host element.

ng generate directive numeric

import { Directive, HostBinding, HostListener } from '@angular/

core';

@Directive({

selector: '[appNumeric]'

})

export class NumericDirective {

@HostBinding('class')

currentClass: string;

@HostListener('keypress', ['$event'])

onKeyPress(event: KeyboardEvent) {

const charCode = event.key.charCodeAt(0);

if (charCode > 31 && (charCode < 48 || charCode > 57)) {

this.currentClass = 'invalid';

event.preventDefault();

} else {

this.currentClass = 'valid';

}

}

constructor() { }

}

Every time the user presses a key,

we extract it from the $event object,

convert it into a Unicode character using the charCodeAt method of the string prototype

and check it against non-numeric code.

If the character is non-numeric, we call the

“preventDefault” method of the $event object to cancel the user action and roll back

the input element to its previous state.

At the same time, we set the respective CSS class to

the input element, valid if the key is numeric, and invalid if it is not.

Apply

<input appNumeric></input>

dynamic view rendering

TemplateRef: The Angular generated ng-template element of the

embedded view.

ViewContainerRef: The container used to insert the embedded view, which is

adjacent to the host element

We can get an instance of each one by injecting them into the constructor of the directive:

constructor(private tmplRef: TemplateRef<any>, private vc:

ViewContainerRef) { }

Assume we pass to the component-template some roles

<div *appPermission="['admin', 'agent']"></div>

In the component, the viewContainer is then used to render views dynamically.

Depending on the appPermission content.

ngOnInit() {

if (this.appPermission.indexOf(this.currentRole) === -1) {

this.vc.clear();

} else {

this.vc.createEmbeddedView(this.tmplRef);

}

}

Files

| .angular-cli.json | Angular CLI loads its configuration here. Technically, you’re not required to use Angular CLI to develop an Angular application, but its many features can highly improve the quality of your code and save you a lot of time along the way. |

| protractor.conf.js | Protractor configuration. Protractor is the end-to-end testing solution for angular apps. |

| karma.conf.js | Is the unit test configuration files. |

| package.json | Npm dependency packages that are identified in a package.json file. |

| tsconfig.json | The presence of a tsconfig.json file in a directory indicates that the directory is the root of a TypeScript project. |

| tslint.json | When using the CLI or many third-party tools, a file named tslint.json or tslint.yaml is used to configure which rules get run and each of their options. https://palantir.github.io/tslint/usage/configuration/ |

Glossary

Component and its Selector

Reusable piece of code, which can be embeded into HTML templates in form of HTML tags

Angular matches HTML tags with components via a selector. It is the name that you give to a component so that it is correctly identified in HTML:

<app-hello-world></app-hello-world> <app-root></app-root> ...

The component stub can be generated.

Also under a “NGModule”, in a subfolder. Here component heroList under module and subfolder heroes.

ng generate component heroes/heroList --module=heroes

Decorator

Java like annotations. Metadata added to the class.

@Component({

selector: 'app-hello-world',

templateUrl: './hello-world.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./hello-world.component.css']

})

Templates

The HTML content of a component is called the template and is defined in the templateUrl property. It denotes the path of the HTML file of the component relative to the component class file:

See the reference to the template in the decorator above.

templateUrl: './app.component.html'

Template tags, mustache tags

Variables, defined in Components can be referenced in templates:

The {{ }} syntax is one example of the Angular template language, called interpolation.

It reads the name property of the component class,

converts its value to text,

and renders it on the screen.

constructor() {

this.name = 'Felipe'; // set the name

}

<p>

Hello {{ name }}

</p>

constructor() {

this.names = ['Ari', 'Carlos', 'Felipe', 'Nate'];

}

<ul>

<li *ngFor="let name of names">Hello {{ name }}</li>

</ul>

Property binding

The property inside square brackets is called the target property and is the property.

The variable on the right is called the template expression and corresponds to the public title property of the component.

// property binding

<span>{{ title }}</span>

// same as

<span [innerText]="title"></span>

Notice that we bind to the Document Object Model (DOM) property of an element, not an HTML attribute

Note:

When we open a web page in the browser, it parses the HTML content of the page and converts it into a tree structure, the DOM. Each HTML element of the page is converted to an object called a node, which represents part of the DOM. A node defines a set of properties and methods that represent the API of this object. innerText is such a property, which is used to set the text inside of an HTML element.

HTML attribute vs. DOM property

Attributes are defined by HTML. Properties are defined by the DOM (Document Object Model).

- A few HTML attributes have 1:1 mapping to properties. id is one example.

- Some HTML attributes don't have corresponding properties. colspan is one example.

- Some DOM properties don't have corresponding attributes. textContent is one example.

- Many HTML attributes appear to map to properties … but not in the way you might think!

Component Inputs

The component can receive inputs, when using the component's tag

@Component({

selector: 'app-user-item',

templateUrl: './user-item.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./user-item.component.css']

})

export class UserItemComponent implements OnInit {

@Input() name: string; // <-- added Input annotation

Usage

<ul> <li *ngFor="let name of names"> <app-user-item [name]="name"></app-user-item> </li> </ul>

NGMOdule

You have to declare components in a NgModule before you can use them in your templates. You can think of an NgModule a bit like a “package” and declarations states what components are “owned by” this module.

@NgModule({

declarations: [

AppComponent,

VideoItemComponent

],

imports: [

BrowserModule, HttpModule, RouterModule

],

providers: [],

bootstrap: [AppComponent]

})

export class AppModule { }

- declarations: The components, directives, and pipes that are registered with the module.

- imports: Other modules that contain declarations to be used by this module. The Angular CLI defines CommonModule automatically for us in this property. It is a module that is always used in Angular applications because it contains all the built-in directives and pipes that we usually would like to use. Be careful not to get caught in circular references when you import a module that already imports yours.

- exports: Angular artifacts that are defined in declarations and are available for other modules to use. This is the public API of the module. It defines what is publicly accessible or not. Everything else that's not explicitly exported would be considered private or internal to the module.

- providers: Services that are provided from the module and are accessible from any module of the application. We'll learn more about providers in the How dependency injection works in Angular section.

- bootstrap: The main component of the application that will be rendered when the application starts up. This property is set only once in the main application module, AppModule, and is usually AppComponent. Typically, you should not change it unless there is a particular reason to do so.

Providers

providers is used for dependency injection. So to make a service available to be injected throughout our application, we will add it here.

Interactions

when the button is clicked, it will call a function called addArticle(), which we need to define on the AppComponent class

<form class="ui large form segment"> <h3 class="ui header">Add a Link</h3> <div class="field"> <label for="title">Title:</label> <input name="title" #newtitle> <!-- changed --> </div> <div class="field"> <label for="link">Link:</label> <input name="link" #newlink> <!-- changed --> </div> <!-- added this button --> <button (click)="addArticle(newtitle, newlink)" class="ui positive right floated button"> Submit link </button> </form>

The #newlink and #newtitle are used, to mark input variables for the addArticle() function.

Typings

JavaScript is untyped, meaning that we can pass around and use data, objects and functions with no constraints. We can write code that calls methods that don't exist on an object, or reference variables that we don't have. These kinds of mistakes can be hard to discover when you are writing code, and it can lead to unstable and buggy code. Doing big changes of your code can become difficult and risky as you don't immediately see if some changes conflicts with the rest of the code somewhere else.

TypeScript is mainly about adding types to JavaScript. That means that TypeScript requires you to accurately describe the format of your objects and your data. When you do that, that means that the compiler can investigate your code and discover errors. It can see that you are trying to call a function with the wrong kinds of arguments, or reference a variable that is not accessible in the current scope.

When you write TypeScript yourself, this formal description of the code is part of the code itself.

However, when you use external libraries like jQuery or moment.js, there are no information of the types in that code. So in order to use it with TypeScript, you also have to get files that describe the types of that code. These are the type declaration files, most often with the file extension name .d.ts. Fortunately people have written those kinds of type declaration files for most common javascript libraries out there.

Typings was just a tool to install those files. It is now best practice to just use npm.

When you have installed those files, which basically only means downloading them and placing them in your project, the TypeScript compiler will understand* that external code and you will be able to use those libraries. Otherwise you would only get errors everywhere.

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/41573822/what-are-typings-in-typescript

# Install Jquery typing npm install --save @types/jquery

Bootstrapping in main.ts

How does Angular know, where to start?

What is responsible for booting up the process of rendering a page on the screen? This method is called bootstrapping, and it is defined in the main.ts file inside the src folder.

import { AppModule } from './app/app.module';

platformBrowserDynamic().bootstrapModule(AppModule)

.catch(err => console.log(err));

Intelij IDEA

Plugin supports syntax highlighting https://www.sgalinski.de/typo3-produkte-webentwicklung/typoscript-phpstorm-webstorm-intellij/?utm_source=phpstorm&utm_medium=banner&utm_term=typoscript%20plugin&utm_campaign=phpstorm-typoscript

To have a support for the Idea, you should:

- node installed on the same machine as Idea, with aws-cli installed globally (npm install -g angular-cli)

- create the Angular project via Idea (File > New > Project > Static Web > Angular CLI) to avoid all kind of errors with work dir and not finding the “ng” executable

- add some arguments to the start script in package.json (“start”: “ng serve –port 5230 –host 0.0.0.0 –liveReload true –open true”)

- Run via Run > Run “Angular CLI Server”

Then the Browser should automagically pick up all changes, made in Idea

Packaging

Angular code pieces - can be packaged as a libs.

Both libraries and applications are modules a the end of the day. Their main difference is how they are built and deployed. A library can be packaged and published for easier reuse across projects. An application includes browser specific files for deploying and running in the browser.

In this article we will explore what happens when we build our library, package our library using npm pack. We'll also see how to actually use our library in a separate application. https://indepth.dev/the-angular-library-series-building-and-packaging/

IDE Intellij

Plugin supports syntax highlighting https://www.sgalinski.de/typo3-produkte-webentwicklung/typoscript-phpstorm-webstorm-intellij/?utm_source=phpstorm&utm_medium=banner&utm_term=typoscript%20plugin&utm_campaign=phpstorm-typoscript

To have a support for the Idea, you should:

have node installed on the same machine as Idea, with aws-cli installed globally

npm install -g angular-cli)

create the Angular project via Idea (File > New > Project > Static Web > Angular CLI) to avoid all kind of errors with work dir and not finding the “ng” executable

add some arguments to the start script in package.json

("startdev": "ng serve –port 5230 –host 0.0.0.0 –liveReload true –open true")

You can then add a Profile / Edit Configuration

Profile > npm Command : run Script : startdev Arguments: -- --host 0.0.0.0 --liveReload true --open true

Run via Run > Run “startdev”

Then the Browser should automagically pick up all changes, made in Idea

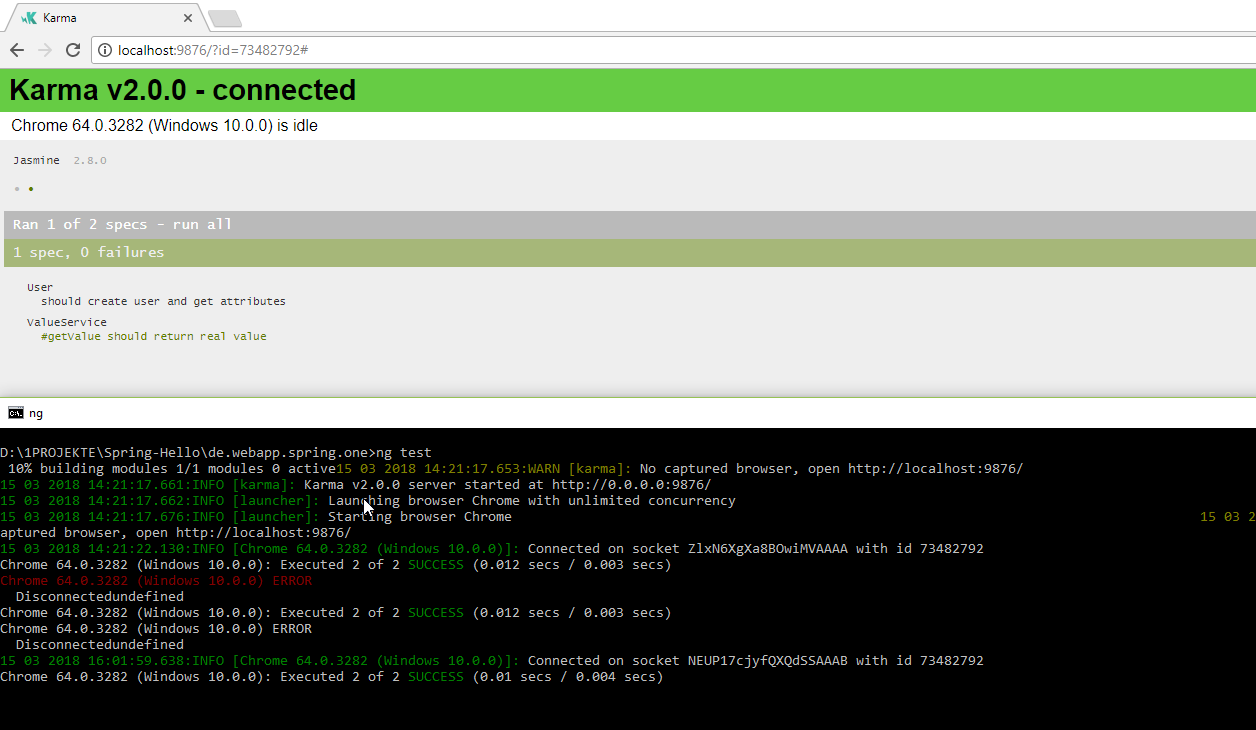

Unit tests

Unit-tests in Angular are using Jasmine.

Config file

| test.ts | This file is required by karma.conf.js and loads recursively all the .spec and framework files. It is referenced by .angular-cli.json. "test": "../../test/angular/test.ts", |

| tsconfig.spec.json | Describes where to look for the unit tets: "include": [

"../../../**/*.spec.ts",

"**/*.spec.ts",

...

|

The jasmine unit-tests are started via:

ng test

which opens a browser window with html results and a console. The coolest thing is, that they stay open and recompile every time, when something changes.

End to End tests

Protractor is an official library to used for writing E2E test suites with an Angular app.

It’s nothing but a wrapper over the Selenium WebDriverJS Api that translates its succinct code and methods to WebDriver JS methods. That said, you can use WebDriverJS methods too inside your e2e script.

Details: protractor

Typescript

Typescript intro in 5 minutes https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/typescript-in-5-minutes.html

Primitive types: https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/basic-types.html

| boolean |

| number |

| string |

| null |

| array |

| tupel |

| Enum |

| any |

| void |

| never |

| object |

Component Lifecycle

Async patterns

Promises

- They cannot be canceled.

- They are immediately executed.

- They are one-time operations only; there is no easy way to retry them.

- They respond with only one value.

private onComplete() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve();

}, 2000);

});

}

private setTitle = () => {

this.title = 'Hello Angular 10';

}

constructor() {

this.onComplete().then(this.setTitle);

}

Observers

// triggers every 2 sec his observables

title$ = new Observable(observer => {

setInterval(() => {

observer.next();

}, 2000);

});

private setTitle = () => {

const timestamp = new Date().getMilliseconds();

this.title = `Hello Angular 10 (${timestamp})`;

}

constructor() {

this.title$.subscribe(this.setTitle);

}